Slavin: I still remember our first meeting at a campus-wide arts gathering: we were both very excited about the possibility of creating connections between art and medicine.

Howell: Absolutely. Over the last eight years I have become even more convinced of the value of arts and medicine for each other. The Medical Arts Program was founded on the belief that the arts—whether visual art, music and performing arts, literary or theatrical ones—are valuable for training physicians who will provide high-quality, humanistic clinical care.

Slavin: Historically, some leading programs have focused on observational skills and these remain foundational to working with the visual arts. However, in our work together, we have ranged quite widely into topics and concerns such as working in teams and with multiple perspectives, empathy and patient communication, understanding social context and cultural competence, and in particular, the issues of complexity and ambiguity.

Howell: When people first train as physicians, it can be very difficult to accept and deal with the ambiguity and uncertainty that are a pervasive part of medical care. Plus we are dealing with human beings. Sometimes our patients die, and interacting with people at the end of life leads to some of the most difficult challenges that young physicians face.

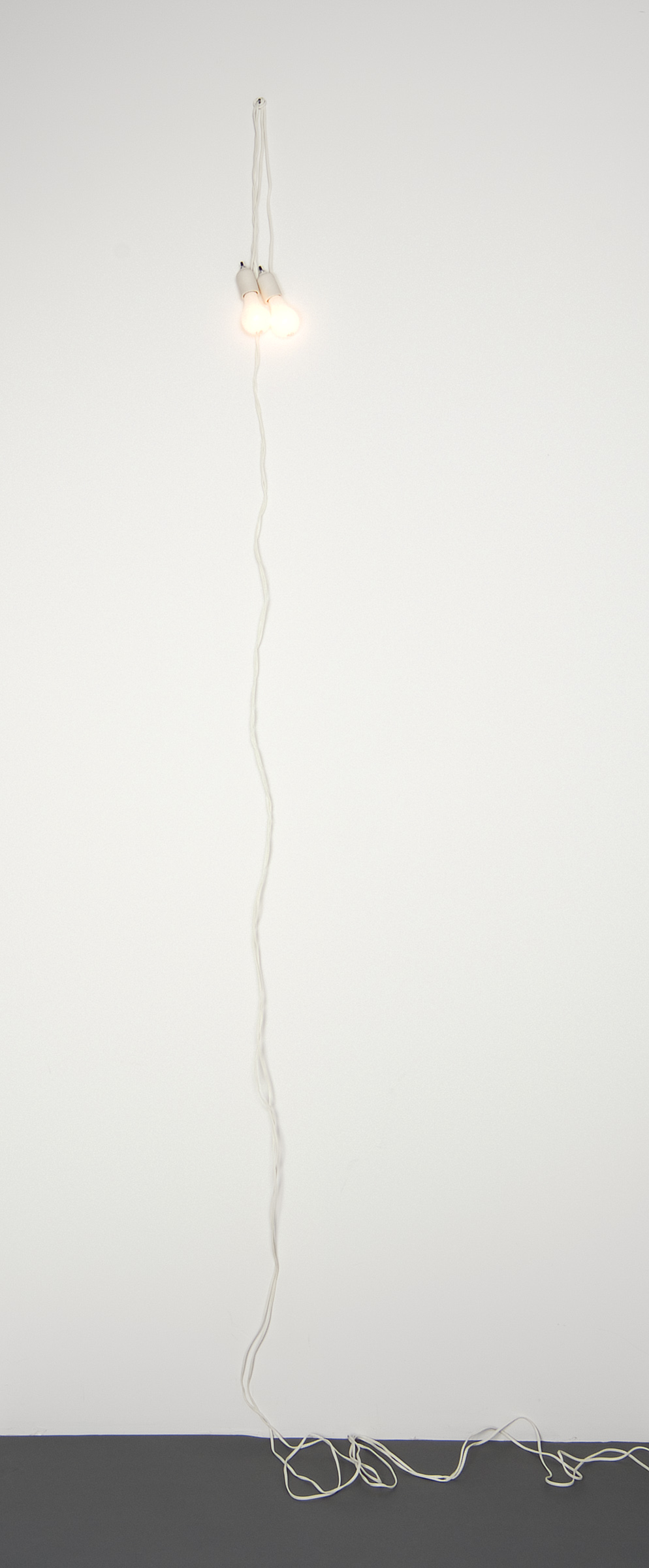

Slavin: Some of our teaching together has explicitly focused on mortality, often using contemporary and conceptual art to invite quite open-ended discussions with medical students—the works of Félix Gonzáles-Torres have proven especially compelling for starting discussions.

Howell: I have loved teaching with those works. The Félix Gonzáles-Torres light bulb work at UMMA—which frankly I would have walked right by—has become one of my favorite works. This installation has been fruitful for so many important discussions. What do you do when you don’t understand or don’t like a patient? Or when you encounter difficult, hard to understand patients.

Slavin: In the Medical Humanities Path, we have experienced the impact of such discussions on successive cohorts of medical students. Recently, we worked with our initial 2015 cohort, who had moved from the classroom into the clinical clerkships. It was quite an experience: we asked students to find a work of art in UMMA’s Tisch Modern and Contemporary galleries through which to reflect on and recount stories of the last few months.

Howell: This simple request led to some extraordinary discussions, which nicely demonstrated the power of art. For example, some students chose the same work but reflected on very disparate experiences, ranging from encountering both death and life on the transplant team, to working with a favorite patient facing a terminal illness. Students also discussed the experience of constantly being watched and judged, or even treated as largely irrelevant. Through the intermediary of specific works of art, they shared stories that continued to resonate with them, as well as those experiences that stymied or frustrated them.

Slavin: It was an intensely focused experience, yet there was also a lot of laughter and empathy.

Howell: Senior physicians were struck by the fact that these stories wouldn’t come out in the busy environment of the hospital. Yet they did in the UMMA galleries, providing insights that were valuable for the students to articulate and for teachers to hear.

Image credit: Félix Gonzáles-Torres, Untitled (March 5th) #2, 1991, 40-watt light bulbs, extension cords, porcelain light sockets. University of Michigan Museum of Art, museum purchase made possible by the W. Hawkins Ferry Fund, 1999/2.17